Jin-class nuclear submarine of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy. (Photo: Mark Schiefelbein / POOL / AFP)

Speculation is rife that the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) will open its second naval base in Africa on the Atlantic coast. The base would be part of China’s drive to become a global military force capable of projecting power far from its shores. Commonly rumored locations include Equatorial Guinea, Angola, and Namibia.

Executives of overseas Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have pushed for a more expeditionary PLA in Africa. Africa alone hosts over 10,000 Chinese firms, one million Chinese immigrants, and approximately 260,000 Chinese workers, mostly working on the One Belt One Road (known internationally as the Belt and Road Initiative)—China’s strategy to link global economic corridors to China.

Port Victoria, Seychelles. (Image: Piqsels)

China’s future military basing scenarios raise numerous questions. Africa has strong reservations against foreign basing, as evidenced by a 2016 African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council decision warning countries to be “circumspect” about permitting more bases. An increased PLA presence could prompt others to follow suit and accelerate transforming Africa into a turf for external competition. India’s efforts to construct security facilities on Agaléga Island in Mauritius, for example, are believed to be in response to China’s growing presence in the Indian Ocean.

Africa’s experience with foreign bases has had its share of controversy. In March 2021, Kenya witnessed a public uproar over the accidental burning of 12,000 acres of land—including a wildlife conservancy—during a military drill conducted by the British Army Training Unit-Kenya (BATUK). The Kenyan press, civil society, and courts have closely scrutinized BATUK’s activities—for a complex that spans hundreds of thousands of hectares—the only overseas location where British battle groups can train on such a scale.

Yet such oversight is the exception. For the most part, African citizens are unaware of the presence of foreign troops in their countries or of bilateral defense agreements. The PLA base in Djibouti is one example. China had denied it was in talks for a military base until construction started in 2016—the same year the AU warned about foreign bases. Initially presented to the public as part of a series of civilian complexes, the Chinese-built Doraleh Multipurpose Port was subsequently expanded to include a naval base. China now has 2,000 troops permanently stationed at the Djibouti base and has completed a pier that can accommodate an aircraft carrier, allowing China to project power beyond the Western Pacific.

Hence, many Africans feel China was not forthright about its true intentions. Beyond the base’s stated purpose of supporting Chinese antipiracy and peacekeeping deployments, very little is known about it and the PLA’s in-country activities. And unlike in the case of BATUK, citizens are unaware of the security agreement between China and Djibouti as Djiboutian courts and media are not as independent.

Should China establish a base on the Atlantic, it would underscore China’s continued push for greater power projection. It would also redefine China’s global posture and Africa’s role in it.

China’s Investments in Expeditionary Capabilities

Chinese military analysts have debated its foreign basing scenarios since the early 1990s, and all Chinese defense white papers since then have called for improving overseas logistical facilities to accomplish “diversified military tasks,” including in 2019 with regard to “far seas” forces.

The goals the PLA have emphasized in these discussions on modernizing China’s naval capacity include:

- Imposing unacceptable costs on the ability of China’s adversaries (principally the United States and its allies) to access and maneuver in the western Pacific.

- Establishing China as a leader in contributing to global security commensurate with its perceived status as a Great Power, particularly with regard to antipiracy, peace missions, and disaster relief.

- Advancing China’s escalating global interests, particularly those associated with the One Belt One Road Initiative, including infrastructure, assets, personnel, and control over sea lanes.

- Closing gaps in matching Chinese capabilities with those of more advanced militaries.

In pursuit of these goals, the PLA shifted from “near coast active defense” to “far seas maneuvering operations” (yuanhai jidong zuozhan nengli, 远海机动作战能力). Several terms of art were coined to benchmark China’s constraints in achieving a more expeditionary force. The “two inabilities” (liǎnggè nénglì bùgòu, 两个能力不够) says the PLA’s ability to win modern wars is insufficient and its commanders are not up to the task. The “two big gaps” (liǎnggè chājù hěn dà, 两个差距很大) speaks of huge gaps in power projection between the PLA and the U.S. military in particular.

Such self-assessments are heavily socialized across the chain of command. In 2013, Colonel Yue Gang, then working in the Central Military Commission’s Joint Staff Department, wrote that the PLA’s transport capacity could not sustain large scale overseas operations and China’s forward military presence was weak compared to the U.S. Navy, which is “deployed worldwide and … capable of engaging in peacekeeping missions or wars in coastal regions.”

In 2015, Zhou Bo, from the Academy of Military Science, China’s most respected military research institute, said the PLA “hasn’t all of the capabilities required to safeguard” overseas interests. Chinese President Xi Jinping has instructed the force to resolve such perceived deficiencies by 2035, when China’s current phase of military modernization is slated to be completed.

The Chinese destroyer Ürümqi sets out as part of a Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy mission in the Gulf of Aden and the waters off Somalia. (Photo: Liu Zaiyao / Xinhua via AFP)

In line with its modernization directives, the PLA has invested in more sophisticated capabilities with greater strategic reach and lethality, including newer classes of nuclear-powered submarines armed with cruise and ballistic missiles. China has also built new destroyers, frigates, fighter aircraft, amphibious ships, navy helicopters, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for longer-range strike and reconnaissance.

Many new weapons and platforms were tested and employed in African waters during antipiracy missions in the Gulf of Aden that started in 2008—China’s first deployments outside the western Pacific. These include the Jiangkai II guided missile frigate, Yuan-class nuclear submarine, Luyang–class destroyers, Z-9C anti-submarine warfare helicopters, Yuchao–class amphibious dock, and improved Fuchi-class replenishment ships.

China’s aircraft carrier program—which began in the mid-1990s— is a further signal of its intention to build power projection capabilities. Its first carrier, the Liaoning, entered service in 2012. It is a retrofitted Ukrainian (Soviet) carrier that China used to familiarize its sailors with carrier operations. In 2019, the first Chinese-built aircraft carrier, Shandong, entered service. A second one will be commissioned in 2022. A Chinese carrier strike group has not yet sailed to Africa, however, commercial satellite imagery suggests that the recent upgrade of piers in Djibouti are large enough to hold aircraft carriers in the future.

“Africa is a testing ground for China’s “far seas” operations.”

Africa also provided the venue for the PLA to gain experience in its first “out of area” operations. Since 2008, China deployed 40 naval task forces to Africa and escorted 7,000 Chinese and foreign ships. In 2011 and 2015, it evacuated stranded Chinese in Libya (35,000) and Yemen (571), respectively.

These operations featured some of China’s newest guided missile frigates: the Xuzhou in Libya, and the Linyi and Weifang in Yemen.

Simply put, Africa is a testing ground for China’s “far seas” operations. Alongside them, the PLA conducts port calls, joint military drills, and offshore military education—improving its interoperability, knowledge of foreign forces, surveillance, and intelligence at a relatively low cost. The PLA’s accumulated experience in African waters arguably positions it for more complex future tasks.

Where Could China Go Next?

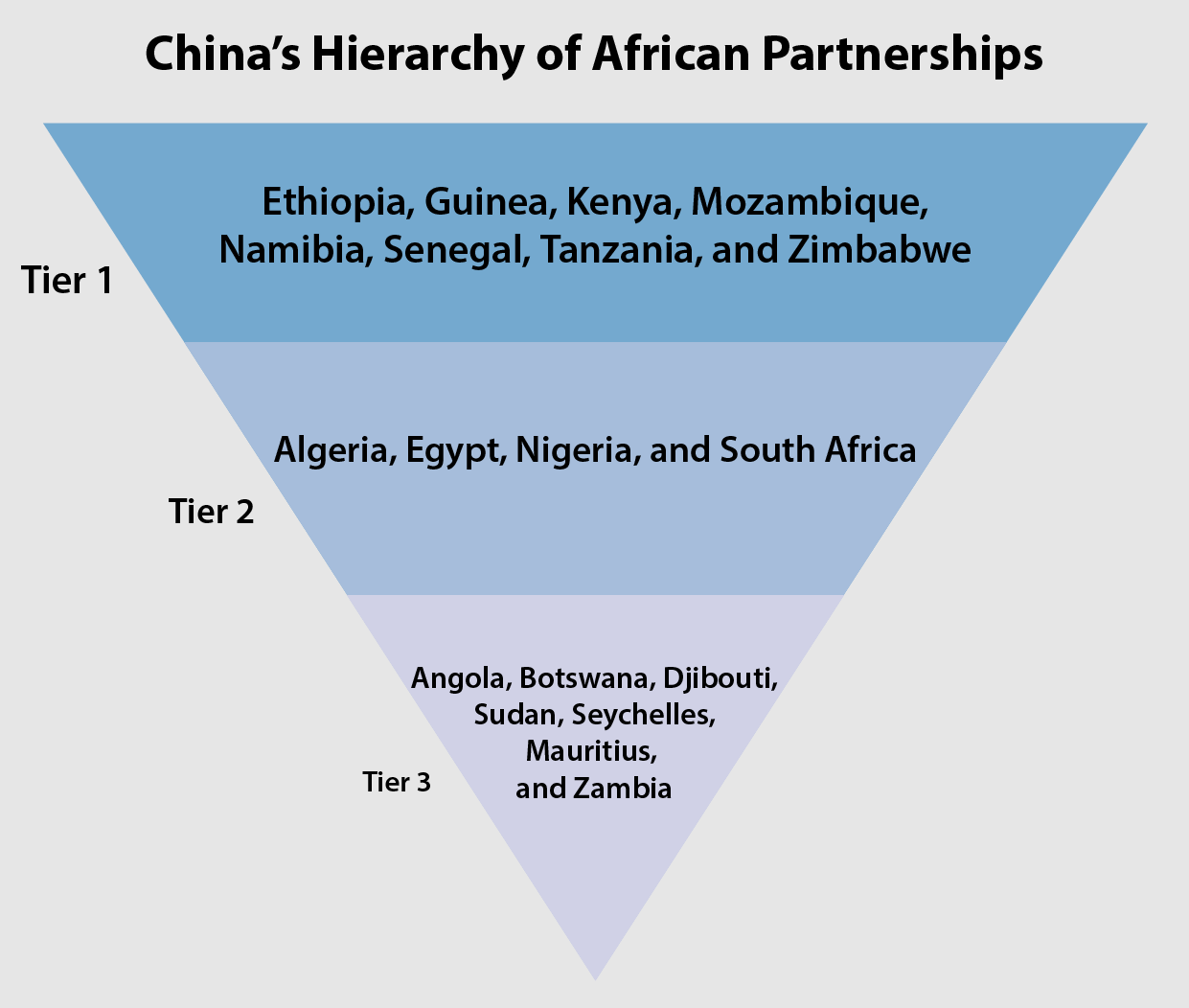

Key to China’s Africa basing considerations is its system of partnership prioritization. This categorization is based on a series of factors such as geostrategic significance, historical ties, One Belt One Road investments, as well as maritime importance. Many of these countries are also leading peacekeeping troop contributors—a plus for China given its tendency to tie its military activities to multilateral missions. This enables it to deflect concerns that its engagements are slowly but steadily becoming more militarized.

China’s top strategic partners also host major One Belt One Road infrastructure projects—including Chinese-built or financed ports—and regularly host PLA Navy port calls and participate in joint drills. Mozambique, Namibia, the Seychelles, and Tanzania receive more than 90 percent of their arms transfers from China. And Kenya and Ghana receive more than half. Some are also among the Chinese Communist Party’s closest partners in the Global South. A 2014 article by the Chinese Naval Research Institute discussed seven ports of interest globally: Djibouti, Seychelles, and Tanzania in Africa—along with Myanmar, Pakistan, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka. Kenya—along with Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)— appears in a 2018 report of the PLA Army Transportation University.

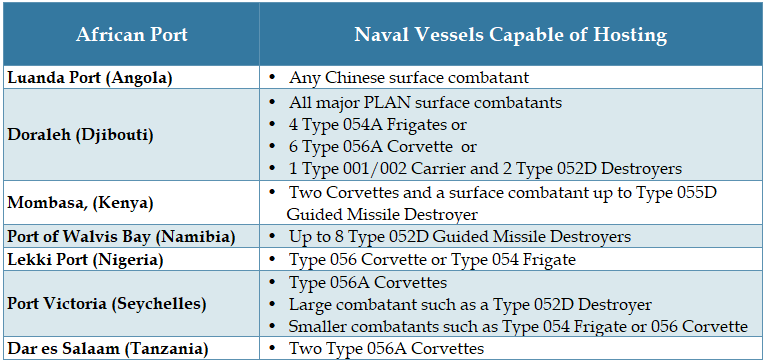

Based on port specifications and PLA Navy port calls, the following African ports can berth Chinese vessels:

Namibia, Kenya, Seychelles, and Tanzania have featured in intense local media speculation as potential basing sites, all of which China has denied. Concerning the Seychelles, China said its presence would “not rise to the level of a ‘naval base’” and would mostly be used for antipiracy missions—the same argument it made to deflect rumors it was planning to open a base in Djibouti.

If China moves forward with any of these locations, it will likely expand the existing civilian port infrastructure and build dual-use facilities as evidenced by the precedent it established in Djibouti. The dual-use basing model entails mixing access to commercial ports and a selective number of military facilities to downplay the military significance of China’s strategic port investments. Needless to say, the PLA has a wide range of options to choose from—46 African ports have either been built, financed, or are currently operated by Chinese state-owned shippers.

“The dual-use basing model … downplays the military significance of China’s strategic port investments.”

As far as regional preferences go, the latest version of China’s capstone doctrinal text, Science of Military Strategy (2020 edition), talks about a “two oceans” approach centered on the Pacific and Indian oceans. According to it, the PLA needs to “create conditions to establish ourselves” in both seas by constructing “maritime strategic support points” (meaning bases) and a “powerful two oceans layout” that can face any crisis. This publication is a useful guide as it is prepared by the Academy of Military Science which reports directly to the Central Military Commission, chaired by Xi Jinping.

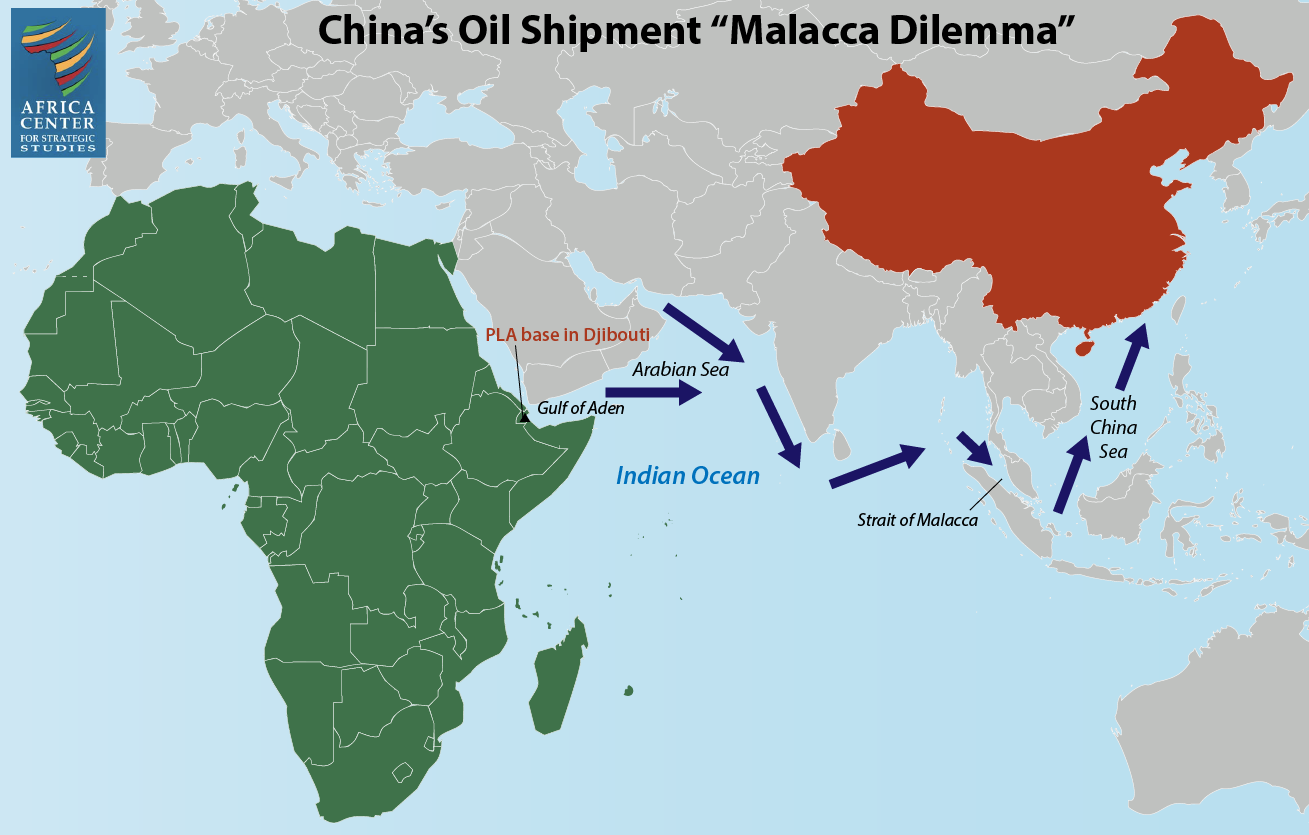

China’s basing strategy in the Indian Ocean partly seeks to solve the “Malacca Dilemma:” China’s Middle Eastern and African imports (including 80 percent of its oil) traverse Indian Ocean sea lanes patrolled by potential adversaries—principally the U.S. Navy. According to the Science of Military Strategy, “They [Malacca Straits] are not owned or controlled by us. Once crisis starts, our sea transport has the possibility to be cut off.”

Several mitigation strategies focused on this dilemma have been published in Chinese military journals over the years. A prominent one by analysts from the PLA Military Transport Academy advocates for “enhanced port construction in the Indian Ocean under the Belt and Road Initiative,” particularly Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania. These port clusters—along with Djibouti and Kenya—would provide new “route options into China to reduce transport pressure on Malacca” and avoid waterways that could be closed by adversaries.

What Do African Stakeholders Say?

Africans are sharply divided over foreign bases on their soil. Some African governments tend to view them as opportunities to prop themselves up and gain additional income. Citizens tend to be more circumspect judging from how they have reacted when they learned of moves to establish new bases. For example, in June 2018, the Seychelles Parliament rejected a bilateral agreement allowing India to build naval facilities after heavy public disapproval led to protests. Similar misgivings were raised in Kenya in 2020 when media agencies reported that China was planning to build a new base. While the claims remain contested, the tone of reporting suggests Kenyans will not be enthusiastic about new military facilities. This closely tracks with sentiments in other African countries given the mixed views associated with foreign military interventions and the aversion held by many about Africa becoming a pawn in geostrategic rivalries.

“Africans are sharply divided over foreign bases on their soil. Some African governments tend to view them as opportunities … citizens tend to be more circumspect.”

Most Africans view China’s influence as positive, in part due to major investments in infrastructure, agriculture, education, and professional training. This could change if China starts to be viewed as a military power focused on flexing military muscle as opposed to a development partner.

China’s future basing options are likely to encounter another challenge. While Djibouti offers a template that can be replicated in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans, its unique status as a host to several other militaries is not readily applicable to other countries. This means China’s next base will not have similar diplomatic cover and will therefore stand out and stoke more controversy than is currently the case.

The level of press freedom will also shape how much scrutiny a future Chinese base will face from its African hosts. China’s future basing scenarios are unfolding when the demand for democracy in Africa is as strong as ever (79 percent reject one party rule according to Afrobarometer) and pressure to hold governments and their foreign partners to higher and stricter standards is growing. A business-as-usual approach where bases are stationed without public input and foreign troops are above accountability is becoming increasingly untenable.

Additional Resources

- Christopher Colley, “A Future Chinese Indian Ocean Fleet?” War on the Rocks, April 2, 2021.

- Paul Nantulya, “Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on: “China’s Military Power Projection and U.S. National Interests,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, February 20, 2020.

- Paul Nantulya, “Implications for Africa from China’s One Belt One Road Strategy,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 22, 2019.

- Phillip C. Saunders, Arthur S. Ding, Andrew Scobell, Andrew N.D. Yang, and Joel Wuthnow, (eds.), “Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms,” (Washington DC: National Defense University Press, 2019).

- Liza Tobin, “Underway—Beijing’s Strategy to Build China into a Maritime Great Power,” National War College Review 71, no. 2, 2018.

- Monica Wang, “China’s Strategy in Djibouti: Mixing Commercial and Military Interests,” Asia Unbound (blog), Council of Foreign Relations, April 13, 2018.

- Bonnie S. Glaser, “The PLA Navy’s Growing Prowess: A Conversation with Andrew Erickson,” Podcast, Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2015.

- Christopher D. Yung and Ross Rustici with Scott Devary and Jenny Lin, “‘Not an Idea We Have to Shun’: Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements in the 21st Century,” China Strategic Perspectives 7, Institute for National Strategic Studies, October 2014.

- Christopher D. Yung and Ross Rustici with Isaac Kardon and Joshua Wiseman, “China’s Out of Area Naval Operations: Case Studies, Trajectories, Obstacles, and Potential Solutions,” China Strategic Perspectives 3, Institute for National Strategic Studies, January 2011.